John Cleese

You see, I think why some of the more extreme woke people think there’s something wrong with humor is they think that it’s critical.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah.

John Cleese

And it is. Because if you have a character who is perfect, who is wise and kind, and there’s nothing funny about him. So it’s only when there are egotisms come out that we laugh at those, which is kind of good for the human race, if you see what I mean. We still find pomposity and greed funny. That’s basically a very good thing. But they say, no, no, it’s critical, so it must hurt people. And then I say, have you ever heard of someone laughing at themselves? Would they do that if it hurt?

Elizabeth Rovere

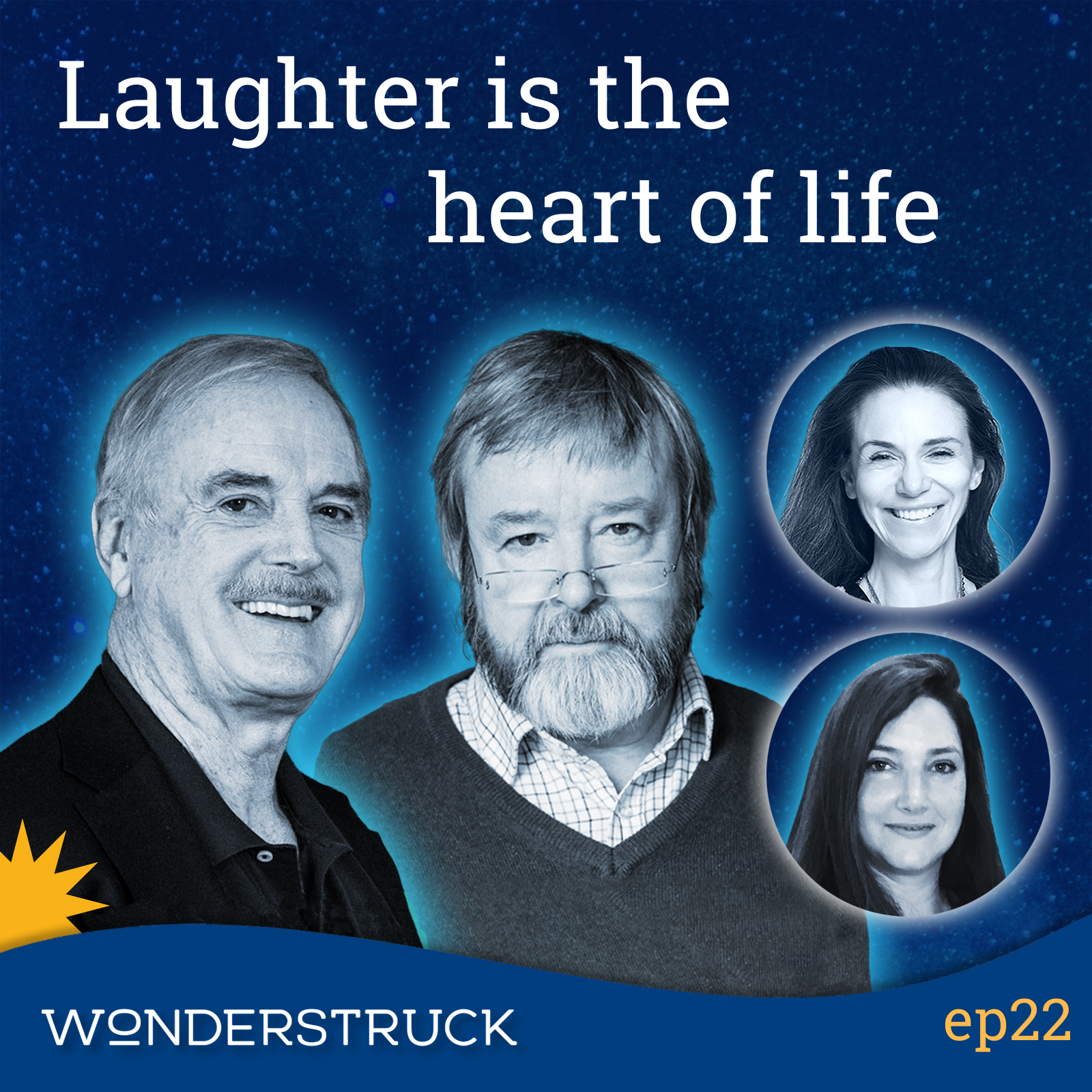

Have you ever thought a joke could transform your worldview? When you think of John Cleese, I’m sure you have a favorite Monty Python episode or a show that comes to mind. What you probably didn’t know is that he’s deeply fascinated by the study of consciousness, neuroscience, as well as the psychological and the philosophical power of humor. In this episode, John Cleese joins Dr. Iain McGilchrist, the renowned author of the Matter with Our Brains, Our Delusions and the Unmaking of the World, with me and my colleague, Mary Attwood. She’s the director of channel McGilchrist and the co-director of the center for Myth, Cosmology and the Sacred. We explore the interplay between comedy, consciousness and creativity and how we can use humor to navigate absurdities, break rigid thinking patterns and foster deeper connections. I’m your host, Elizabeth Rovere, a clinical psychologist, yoga teacher and graduate of Harvard Divinity School. I am forever curious about experiences of wonder and awe and how they transform us. With Wonderstruck, we invite you to explore these ideas through conversations with experts and experiencers across various disciplines and perspectives. Welcome to wonderstruck. Today we have a wonderful four-person podcast. I’ve got my colleague here, Mary Attwood, and we are going to be interviewing and have having a dialogue or a quadrilog with Iain McGilchrist and John Cleese. So welcome everyone.

John Cleese

That’s Iain.

Mary Attwood

Thank you.

John Cleese

I’m the John.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

It’s welcome from me and it’s welcome from him.

Elizabeth Rovere

So I think really the first question that I would like to ask you is how do you all know each other? How did you meet?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I can quite vividly. A friend of mine wrote to say he’d been sitting in his CEO’s waiting room and picked up a magazine and in it there was an article with a picture of you holding the master and his emissary. And underneath it said, John Cleese is telling anyone who will listen that this is the most important book. And so, I thought, oh, gosh, that’s rather nice. And he didn’t know how to contact you, so I wrote your agent and said, I gather John likes my book. If he’s willing to give me a call, we can talk. And I went away for a few days and when I came back, I went through my answer machine and all those things going, deliver on Tuesday. And then there was, hello, this is John Cleese. This is like God Almighty is talking to me. This is John Cleese. I just want to say that your book is the most. The most important book I have ever read. I thought, oh, gosh, this is good. And I think shortly after that, we may have met. But I think the next thing I remember is you taking part in that film, the Divided Brain, about my work, which you were kind enough to grace me.

John Cleese

Well, I just think it’s an incredibly important book I always have because it explains to me a whole lot of things that I never understood before and that you can’t give higher praise to a book than that. And then we met up and the nice thing is you’re serious. No, we laugh the whole time. We’re very silly and we mutter subversive things to each other during conferences.

Elizabeth Rovere

That’s fantastic. Have you been doing that here?

John Cleese

Yes, very subversively. Excellent, excellent. So, what are you going to ask us?

Mary Attwood

Well, we’ve got a series of questions from the participants here at this symposium. And. And they’re very happy for us to acknowledge them and their names and. And that they are the instigators of these questions.

John Cleese

So they don’t wish to remain anonymous?

Mary Attwood

They don’t.

John Cleese

Which is a good sign.

Mary Attwood

That is a good sign. Well, just a very sort of minor question to start with, a very small point. Is humour woven into the fundamental fabric of the cosmos, open to both?

John Cleese

What a lot of people say, is life a comedy or a tragedy? And I think it depends on your mood because you can see it as a total tragedy. You can see it as really very funny. I think it’s probably to do with your attitude to death, isn’t it?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Could be, yes. Who was it? It was an 18th century Frenchman, probably Voltaire, who said, life is a comedy to those who think and a tragedy to those who feel. Oh, something of that, but I agree with you. But if humour is not woven into the cosmos, I need to know why not? Because it seems to me a very fundamental feature.

John Cleese

Absolutely.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And what I love About Zen is that it’s able to espouse humor in a context of something that is about the ultimate context of our existence. And I always say that people like you, John, are up there for me with the poets. And that’s saying a lot because, you know, I’m a great lover of poetry. But I think there’s a lot of.

John Cleese

Taught it at Oxford.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I sort of did, yes. And I think that this. Something incredibly important about it. And as I get older, I mean, humor is the main thing that keeps me going, actually. I mean, just laughing at the absurdity of so much that happens.

John Cleese

I think I was brought up, you see, with a very. I was at Cambridge, and everybody was snotty. You know, everyone was trying to pretend they were smarter than everyone else. And I remember at that time just thinking how democratizing a force humor was. Because if you had a group of people sitting there all laughing together, there’s no hierarchy. And I think this is why dictators and pompous people hate humor. Because their pomposity just go when they’re in a humorous atmosphere. So they want everyone to be solemn. And in that context, I have to say, the funniest thing I’ve seen for many months was the coronation. My wife asked me in to watch it with her cats. And I sat down just as Charles was coming into the cathedral. And I laughed solidly for about 10 minutes. I thought it was so funny. These people in these ridiculous cultures had everybody pretending it was very solemn and important. I couldn’t stop. So I think that it’s terribly important to have that. It’s as though. Well, it’s right, because Bergson says, doesn’t he, about humor, that it requires a momentary anesthesia of the heart in actually one moment. You just have not to feel when. Which is it? Tom and Jerry. Jerry, which is the cat? Tom.

Mary Attwood

Tom’s the cat.

John Cleese

So when Jerry runs Tom over with a steamroller, you know, you can laugh at that because you can’t be thinking how that poor cat must be suffering. Do you see what I mean?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I do.

John Cleese

In real life, when you’re running dogs over for a laugh, which is what I did in Fish Caught Wanda, people were able to laugh at that because it was just an idea. You see what I mean? It’s just an idea. And also because they were Yorkshire Turret, because if they had been German shepherds, we wouldn’t have got away with it. But we did at a very early screening. We put in a shot with some sort of flattened dog with a bit of blood. And it Totally killed the laughter because suddenly it became real. And you can’t laugh at a squashed dog in reality, but you can laugh at the idea of it. And I think that laughing at the idea of things is extraordinarily important for.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I think, our mental health, but also for civilization. One of the things that worries me, and I’m sure worries you, is the way in which humor is now censored on so many fronts, because there are things you’re just not allowed to joke about. But actually there’s nothing so serious, or almost nothing, perhaps I should say, so serious that it can’t be made the subject of humour. And humour is a great civilizer, as you say. It’s a sort of leveler. It means the pompous have their balloon pricked a bit. And it means that actually a sense of proportion comes into this and that you can talk with that person and it defuses tension. I mean, the idea is that somehow humour will give rise to aggression. Very often it has the exact opposite effect. It kind of calms things down. People have a laugh and then the. The tension that has gone.

John Cleese

But pompous people see it as aggressive because it destroys their feeling of importance.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

It’s the enemy of self-importance. Yes.

Elizabeth Rovere

Which means it’s a sign of mental health to be able to laugh at yourself. And it’s like, I think about the comedian and the poet and the prophet, like getting away with being able to say things right, as long as it’s not too pompous of a person that’s not going to be able to hear it. But sometimes you can get away with it, which is kind of a gift, you see.

John Cleese

I think why some of the more extreme people think there’s something wrong with humor is they think that it’s critical. And it is. Because if you have a character who is perfect, who is wise and kind, and there’s nothing funny about him. So it’s only when there are egotisms come out that we laugh at those. Which is kind of good for the human race, if you see what I mean. We still find pomposity and greed funny. That’s basically a very good thing. But they say, no, no, it’s critical, so it must hurt people. And then I say, have you ever heard of someone laughing at themselves? Would they do that if it hurt?

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah, exactly.

Mary Attwood

And it stops us from becoming too sensitive as well. You know, this sort of over sensitivity that we’re living with at the moment, I think is.

John Cleese

It’s a very complicated business. I mean, I’ll tell you one thing which I think is, it was a big lesson for me. I was in Bosnia, I was in Sarajevo and they were telling me about the four years that they were under siege from the Serbs. Sarajevo’s in a valley and the Serbs were up there lobbing shells down and shooting people crossing the street. Telescopic lens rifles. And they told me an extraordinary thing. They said they found an underground car park and they changed it into a cinema. And they used to go in the evening and watch comedy. I’m proud to say a lot of it. Monty Python. And they said, and this is what struck me when we came out afterwards, we felt better, yet nothing had changed. Yes, the business of laughing had moved themselves to a part of their own mind where they could cope with those appalling circumstances better. And I’m surprised how many people say to me now in my old age, thank you for helping me through difficult times. I’d never have thought of that.

Elizabeth Rovere

That’s so interesting.

John Cleese

They will put a program on if they’ve had a bad day. And I was at a Comic Con recently and one lady leaned forward and she said, well, I just want to tell you that my husband and I had a daughter who was murdered. And she said, we couldn’t sleep for weeks. And then we found if we watched 40 towers before we went to bed, we should. Sorry, we could get some sleep.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Extraordinary.

John Cleese

So it’s got a incredibly positive force which people who don’t understand it are trying to take away from us.

Mary Attwood

I find it fascinating. It doesn’t need analyzing, does it, in terms of the sort of neuroscientific aspect. But I guess in terms of the hemispheres, you can understand it from that point of view. It’s not just a shift in perception, although that’s probably part of it. But what is happening there in terms of somebody being moved and affected by comedy?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well, humour is appreciated in the right frontal region, along with metaphorical meaning, which humor often is playing with, as poetry is. And poetry too is dependent on this area, which is why I feel it’s okay to say, and I believe it, that great comics are like great poets and that they show you something new and it is a blessing. But, you know, the, the left hemisphere’s understanding is literal. And of course, when you take things literally, you can’t any longer see humor. You can’t understand poetry. You don’t understand indirect meaning. And indirect meaning is of course the basis of a lot of comedy and so. And suddenly know shift of gestalt. So you see it another way you looked at it like that and suddenly you see, oh, of course. And that’s again such an important thing for us.

John Cleese

If you wait. I read something that said that comedy is about a change of context.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And context is what.

John Cleese

The perfect example is the woman who’s carrying out a survey of sexual attitudes and she’s at an airport and a very good looking pilot is walking by. She said, could I ask some questions? And at the end she says, may I ask when you last had sexual intercourse? And the guy says 2017. She’s really quite surprised. He says, well, it’s only 21, 22. It’s a perfect, perfect example of change of context.

Elizabeth Rovere

There’s a follow up question to that from Charles Stang, which I think we’ve touched on it a little bit. But speaking to the significance of humor and actually laughing in regard to what we mean by consciousness, how does it fit into the concept or frame of consciousness?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

There is unconscious humor, right? And sometimes one’s dreams can actually be funny. And an example of that is that after I’d seen for the first time, I think it’s episode five of the first series of Fawlty Towers, which is the evening in which the chef gets drunk and you go off and get what purports to be a duck. But I mean, that whole thing was so wonderful and so funny. And I sometimes use that scene where you come back and you have it on the trolley and you’re kind of sharpening the knife and you’re pushing it along with this and you take the lid off and it’s a blumence and you go. And I think this is rather like.

John Cleese

That’s the funniest moment in the whole series is when I do that in the hope that the duck is still underneath the bermo.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I sometimes use that to describe the effect of the decay decoding of the human genome. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a, wow, heroic undertaking. But we thought at the end of it we’d have the secret to all sorts of things. And there’s hardly any information in it. But what happened? Anyway, after that episode I went to sleep laughing and I woke myself up in the morning laughing.

Elizabeth Rovere

That’s beautiful.

John Cleese

I don’t know how it intersects with consciousness, I really don’t because I think so much of it is about what one anticipates as a result of one’s experience. You see what I mean? It doesn’t seem to me to move into those areas.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well, a sudden shift of perspective, which is the thing that. Again, sorry about this, but the right hemisphere is much better at. The left hemisphere gets locked into a point of view and. And can’t see the virtue of a different one. The right hemisphere is much better able to be fluid in this way. And it’s behind almost all humor. And my current favorite joke is from some stand-up comedian who said, it’s not easy being a stand-up comic. In fact, when I told my friends that I was planning to be one, they just laughed at me. They’re not laughing now. Suddenly you get, whoa, brilliant.

John Cleese

I think that when people can only see one interpretation, which is the literal interpretation, they can’t see any others. Well, then it’s not surprising that they’re absolutely sure that they’re right because they can’t see others. Whereas people who can see lots of possibilities but choose this one as the. That’s a much more intelligent point of view. But it won’t be held with the rigid dogmatism. Remember what Barry Goldwater said about arguing with the fundamentalist Christian? Goldwater was not a left-wing firebrand. He ran for president against LBJ in 1964. But he said, it’s impossible talking to those people. And I think it’s because they’re so sure that they’re right, right.

Elizabeth Rovere

There’s no other possible.

John Cleese

They can’t see alternative.

Elizabeth Rovere

Somehow. It reminds me of something I heard the two of you talk about at one point where something about when you lose something, you only look underneath the light to find it. But it’s like there’s so much more in the dark. It’s the same idea.

John Cleese

Do you want to talk about that? Well, I can.

Elizabeth Rovere

You made a joke about it.

John Cleese

Well, when I was 12 years of age being taught French by Mrs. Tolson, she told me the old story about the man who’s walking along and he walks past a street lamp and there’s a guy standing there staring at the pavement. And he says, is it all right? He says, I dropped my keys. He said, we’ll soon find them. And they look around for a bit and the guy said, were you sure you dropped them here? And he said, no, no, no. He said, I dropped them down that alley over there. Why are we looking here? He says, well, the light’s better. It’s quite profound. I think it explains behaviorism because science proceeds by measurement and it hates things that you can’t measure. So, it goes where the light is. Hence behaviorism, despite the fact that it taught us absolutely nothing about human beings.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah.

John Cleese

You see what I mean?

Elizabeth Rovere

Absolutely.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

That’s right. And I sort of contrast the conscious and the unconscious mind in this way that what we call the conscious mind is the spotlight of our attention, which we’re aware of, attending 99.44% quoting here a rather ludicrous figure from an academic paper, but you get the point. Almost all of our awareness is actually outside that field of consciousness. And so it’s. The rest of the playhouse is still there. When you’re focused on this little bit where the light is, it hasn’t gone away, it’s still there.

Mary Attwood

Rachel Peterson has asked what role does humour play in the theory of the mind?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well, I wonder if she means theory of mind or whether she means theory of the mind. This is because theory of mind is a term of art in psychology which means the ability to understand what another person may know that you don’t or not know that you do. So, this is something that is said to develop rather late in children, about the age of three and a half or four, although there’s some evidence that it sometimes happens a lot earlier than that. And it was also thought that animals couldn’t develop theory of mind. It’s quite clear they can. A squirrel notices as it’s being watched. It doesn’t bury its nuts while it’s being watched. It then waits until the person has gone away, then buries them. It kind of understands that this other person’s mind will have in it the information about it. So, these laughter in my book is, I say, very important. And it has various features that are to do with creativity and consciousness. One is this ability to shift perspective. Another is the ability to see hidden information that is not being made explicit. And yet another is to see that there is an incongruity often in life which we’re not aware of if we’re too rigid and make everything systematically coherent. And an awful lot of not the best science, but a lot of the very pedestrian everyday science is so sure that it knows what it’s doing that it doesn’t see things that are actually there for the seeing.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yes.

John Cleese

One of the strange things, it seems to me, about scientists is they’re not usually very interested in the philosophy of science. They don’t want to examine what they’re really doing.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

There are noble handful that are. But you’re right in general, I think, and they consider philosophy a bit of a waste of time.

John Cleese

Yes. Well, they should be getting on doing science. Getting on with doing science, making assumptions they never questioned we scientists, you see, I think that they’re scientists that are always trying to pretend they know more than they really do. So, I have a speech that starts, we scientists now know that we scientists know less than we thought.

Mary Attwood

Wouldn’t that be a thing?

John Cleese

Because people want to think they can explain everything. And I think that’s why contemporary science, so many scientists hate psi phenomena, remote viewing, that kind of thing, psychokinesis, because they can’t explain it.

Elizabeth Rovere

You know, you just read my mind because that was actually the next question.

John Cleese

Oh, good.

Elizabeth Rovere

It really was. It’s like, what about these kinds of really weird events and experiences like psi phenomenon or precognition or whatever, extraordinary phenomenon? How do you fit that into consciousness? Or how do you forget about consciousness? How do you even fit that into your worldview?

John Cleese

I think that because I’ve been interested in it for a long time and I don’t think there’s any question at all that a lot of those phenomena, the existence of them, has been proved beyond any doubt.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

It’s a controversial area. And I think that it’s not good enough to say that standards of evidence are too low because some people, like Dean Radin amongst others, have taken extraordinary precautions that are not made in mainstream science to the same level. So, these are really remarkable attempts to try and get objective evidence and succeed in finding it. The problem is, as somebody was saying the other day, is that the effects are relatively small, although highly significant statistically.

John Cleese

Statistically.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

So what that means is it doesn’t sound stubborn that there’s a better than average chance of this happening. Perhaps instead of it happening 25% of the time, it happens 28 or 9% of the time. But if it does that regularly over long sequences, then there is something there that is statistically highly significant.

John Cleese

I met a man down at University of Virginia, the DOPS Department of Not psi. They’re not allowed to say that. I think it’s perceptual studies. And he was a judge from North Dakota, Large bear like man, very nice. And he was what they call a talented subject. They had a little. A little machine which flashed one of red, blue, green or yellow and you had to guess which it was in advance. And obviously most of us would score 25. Well, he would score 35 or more all the time.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

It’s extraordinary.

John Cleese

So when there’s that kind of stuff. And there was a meeting at the Statistical association in America and the woman who was in charge that year said she’d actually worked on some of this stuff for the US military and a lot of it had been proved, she said, and she was a statistician beyond any possible doubt. But as Iain says, it is statistical. They’re not huge effects, but they’re absolutely undeniable.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

They’re there and therefore required explanation. It’s not good enough to sweep them away. The fact that they’re not immediately replicable always depends on individual differences, partly. So, some subjects just have this gift that the rest of us have suppressed or have been educated out of noticing. And if you see the effects of one’s accustomed way of thinking on what one fails to see right in front of one’s eyes, a famous example is the gorilla in our midst. It was wonderful. Look it up on YouTube if you don’t know it. And there, the most blatant thing is completely misled.

John Cleese

Let me just explain, in case people don’t know that it was a group of students playing basketball, some in white shirts, and they were asked, the audience was asked to count the number of passes made by the people in the white shirts. And while they were passing the ball around, somebody came in dressed in a gorilla suit and stood in the middle and actually did that and walked off again. And a lot of the people didn’t see the gorilla because they were so focused on the passes, counting the passes.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

If we were all taught and educated to exclude certain experiences as possible, we won’t see them. And some individuals are more resistant to that and therefore better subjects. But a point I’d like to make, and this is not in any way disrespectful to science, which is incredibly important, and I am a scientist, and I believe in it, but.

John Cleese

But you believe in good science.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I do. But replication is a problem in mainstream science. It’s not. Not just something that is difficult for people investigating anomalous phenomena, as we would call them. So even in the mainstream, the attempts to replicate experiments are very often completely unsuccessful. Now, all of these things are a matter of proportion, but I just want to bring that in, as we shouldn’t be applying a very different standard to a phenomenon that is demonstrable over a long series as statistically significant.

John Cleese

What I think is extraordinary is that the materialist, reductionist scientists get very angry about this stuff and see it as a threat. Whereas I think at least they should do is say, well, it might be interesting. I hope somebody investigates it further. That seems to be the rational attitude. But when you say, what?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

No, I was going to say there’s a lot here that, sorry, is again, hemisphere relevant because the left hemisphere is not, as supposed in pop psychology, without emotion. In fact, it specializes in anger. So, anger is the most lateralized of all emotions and it lateralizes to the left. And other emotions that lateralize to the left are a sort of disgust and the sense of superiority. So, when you put all these things together with a rigidity of mindset, a mechanical way of thinking, all of these typical of the left hemisphere and there’s nothing wrong with these things, they’re very useful as science. Even mainstream mechanistic science has been very, very useful. But nonetheless if you put that together you see that it is a rigid mindset that is entirely self-coherent. Whereas another mindset which is more typical of the right hemisphere is much more flexible. And interestingly when people have damage to the right hemisphere, they are incorrigible in certain beliefs. Evidence will not sway them. But when people are right hemisphere dependent, they may be getting everything right but they’re still quite questioning whether I’ve really got it right. So, they tend to be over self-critical whereas the left hemisphere types are under self-critical.

Elizabeth Rovere

So if you’re in the. I’m just thinking, going back to the gorilla, you’re conditioned in that way in the left hemisphere dominated society to really not see that, not notice that.

John Cleese

Well, you mentioned recently the effect, what’s it called? The something Jenning Kruger, the Dunning Kruger effect.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Dunning Kruger effect.

John Cleese

And you summed it up wonderfully. Can you.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well just that those who know a lot realize how much they don’t know. But those who know very little think they know it all. But there is another piece of research by Dunning and Kruger which is even better in a way and that’s if you demonstrate to somebody that they’ve got a certain way of doing things that is not working. So you get a university administrators administrator who says, or hospital administrators, this is how we do it. And the evidence piles up that this is not helping. When you present that evidence it doesn’t cause them to waver, it causes them to redouble their efforts at the same thing. And I see this everywhere.

Mary Attwood

But didn’t you say as well that when you were working as a psychiatrist and the more middle management started to come in to sort of tell the nurses this is how things should go but they haven’t had any actual experience experience of having the hands on experience or doing what you were doing which was actually talking to real patients every day and that they were trying to put forward these new ways of doing things through a sort of more, more administrative task that it, that this is the idea they have but actually it’s removing them from the experience altogether and it’s Just an idea that they’re trying to push forward. And I think that’s happening to an extraordinary extent now in a very extreme way that we see across all systems.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Yeah. I was lucky enough to be a sort of protege of Alwyn Lishman, who’s professor of neuropsychiatry at the Maudsley and is sometimes thought of as the person who really kind of founded modern neuropsychiatry. And he told me one day that he’d been questioned by a manager as to why he had sent a pair patient for an MRI scan. And this was a quaternary referral unit that he headed and I was working on. So, this was people who’d been through all the things and this was the last place. And he said when a manager asked me why I’ve made a clinical decision, it’s time for me to leave medicine. And he retired and he did. Great loss. Anyway, let’s have another question.

Mary Attwood

All right, I think let’s have this one. It’s from Anil Seth. Free will. Are we determined to have it?

John Cleese

I never heard that. That’s a good one.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

That’s a nice one.

John Cleese

I don’t know after what has been discovered in quantum physics about the effect that the observer has on the experiment, that the answer depends on the question that’s asked. It’s a true process. I don’t see how you can go on claiming that life is deterministic. Is that simple minded?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I don’t think it’s simple minded. I think there are a number of ways of looking at it. But the one that is most convincing to me is that we know from physics that it is not a matter of not knowing enough to be able to predict what’s going to happen. But intrinsically it is impossible to predict the future if you go far enough down the line. So the idea, the ridiculous 18th century idea that if you knew the position and momentum of every particle in the universe, you could predict every single thing that happened, including what you’re about to say to me. And this is completely untenable because of uncertainty being built into the nature of events in physics.

John Cleese

I was thinking something in volume two of the Matter About Things and it was something about billiard balls.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I’m going to come to that. Oh, yes, yes. The thing that really impressed me was that some physicists sent me a paper on indeterminacy. And the point that is often made by laypeople is that, oh, all that quantum stuff and indeterminacy, it only exists at some very micro level. But many physicists are going around saying, no, it exists all across the board. It’s rather like saying, you know, the earth is round, except everywhere I am at where it seems flat. So they did this thing. If you actually were to do a kind of 18th century experiment of balls hitting one another just to see how much you could predict after a certain number of collisions, you cannot predict.

John Cleese

You said eight in the book, is that right?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

You’re a terrible man.

John Cleese

I’ve read it.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

You’ve just stolen my punchline.

John Cleese

Edit it out.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

When I read that I thought, well, what’s it going to be? How many collisions? Is it going to be a billion or perhaps 10 billion? The answer is 8. 8.

John Cleese

Isn’t that extraordinary?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

It’s a ridiculous idea that anything can be that determined. Even the most mechanistic thing, never mind. When you come to things that involve, as every human act does, so many causative streams, it’s perfectly simple minded.

John Cleese

I always wonder about the cast of mind that wants things to be determined. I was talking to someone half an hour ago.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah, it’s interesting.

John Cleese

Who loves the idea that it’s determined. And I would have thought it was a terribly depressing idea.

Elizabeth Rovere

That’s interesting, right?

John Cleese

Why would you want to believe that?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well, I think only if you were very insecure and wanted certainty about everything. There’s quite a lot of people who have a psyche which craves certainty. But on the other hand we have research on people who believe that they have free will and those who believe that they’re determined. And not only are the people who believe they have free will sort of happier, which you probably expect. But interestingly, the people who believe they are determined have lower moral standards than people who believe that they have independent judgment, must take responsibility for their actions. And I think human life without a sense of responsibility for what you do is terrible. And one of my great heroes, particularly these days is Hannah Arendt.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And one of the things she said is about the evil of totalitarianism is that it makes people feel that they are just machines that follow instructions and they have no self-efficacy.

Elizabeth Rovere

Right. Like it doesn’t necessarily matter what I’m doing.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Let them roll.

John Cleese

Bring on another one.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Yes.

Elizabeth Rovere

Where are we? Okay, so this is from Lucas DeBride. It’s an interesting question. What have you unlearned this year?

John Cleese

I think I’ve unlearned, maybe not this year, but since I was in Sarajevo, that humour’s a luxury. Do you see what I mean? I always used to think, being snotty ex Cambridge, that it was kind of minor. It was making people laugh. And that was good because it was good to laugh. But it ended there. And after Sarajevo, I thought, no, no, it’s much more important than that. And then meeting the people at the comic concert and then, if I may drop a name, when I interviewed the Dalai Lama, I talked about the fact that Buddhists spend so much time giggling.

Mary Attwood

Yes, yes.

John Cleese

At the absurdity of it all, which is wonderful. But what he said, he said something slightly different. He said, what I love about laughter is that when people laugh, they can have new ideas. You see, I think when you’re being creative, that laughter is part, part of being creative. It’s a part of relaxing, it’s a part of play. All these things are the same thing, different aspects of the same thing. And when you’re very relaxed, you will be laughing, you’ll be smiling and laughing. And that frame of mind, you’re much more likely to let a new idea in and to chew it over than you are if you’re sort of cold and defensive.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And also you need to be relaxed to be creative. If you’re given a deadline that you’ve got to produce something by a certain date, it will inevitably be more mediocre because you won’t have time to allow all kinds of possibilities in and explore them.

John Cleese

There’s some wonderful research done in the 60s at Berkeley and among architects, and it showed that the most creative architects, nothing to do with IQ, but they did two things. One was they knew how to play full stop. And the other was they took as long as they could to make their minds up. If that decision had to be made, they’d make it, but they wouldn’t make it before that time, whereas most people do, because they don’t like living with uncertainty. So, you see, if you really crave certainty, you like to make your mind up as fast as possible. And that is very uncreative.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And to be fair, it’s not just the people who are trying to be creative. It’s the imposition of, again, managerial standards, you know, to justify your post. You must have written this by next Wednesday or whatever. And I mean, I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again. I had this incredible luxury and honor of being elected to a fellowship at All Souls when I was 21. It gave me seven years to do anything I liked, no questions asked. And I think I had to write a one side page to the warden saying, I’ve read some books this year sort of thing. And at the time I thought, gosh, you’re really squandering this time because it’s so precious. And as I’ve got older, I thought that was such a gift. You didn’t make use of it, I now think no, because if, as people say, I’m able to draw together strands from various different places and to see things in a new way, I put it down to the fact that actually that time was fallow, it wasn’t wasted, and if I’d been forced to keep producing a result, I’d have crystallized my thinking at age 23. But actually, I didn’t have to crystallize it then. I was allowed to go on evolving it.

Mary Attwood

So that’s just a no PhD you to follow and no sort of monitoring of what you’re doing all the time. I mean, it’s an extraordinary luxury and I don’t think that happens anymore.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

I was going to do a PhD in the history of ideas around the end of the 18th, early 19th century. And Derek Parfit, the philosopher, was a kind man and he said don’t do that, don’t do a doctorate. If you hadn’t got a fellowship here, you’d have to do a doctorate, but because you have this, you don’t have to do doctorate. And it means you can do something that very few people get the chance to do. So that was that.

Mary Attwood

And what have you unlearned this?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

What have I unlearned, Iain? I think there’s been a process over the last few years that has accelerated perhaps over the last year of seeing the true value of value. So, when I was young, I didn’t in any kind of anal way sort of plot the chapters of the matter with things. But I didn’t think I was going to write a chapter on values, having dealt with time, space, matter, consciousness, to then move on to purpose and values. And those things seem to me with every passing year more and more clearly important. And they’re of course things that science perfectly reasonably wishes to disattend to. So, it can’t prove that they don’t exist because it has nothing to say about them.

John Cleese

But it can’t measure them.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

But it can’t measure them. And it very reasonably wants to look at how we go without preconceptions about values and purposes. That’s not a criticism of science, but it is a clear indication of the limits of what science can tell us. So when they say science tells us that the universe is pointless and materially baron and all the rest, it can’t tell you any such thing. And I think back to this wonderful image that C.S. lewis gives in, I think, the preface to Paradise Lost, where he says, it would be like a policeman stopping all the traffic in the street and then writing solemnly in his notebook. The silence in this street is very suspicious.

Mary Attwood

This is a funny one. This is from Mervat Nasser and it’s directed to John, but I think it could also apply to Iain. You call yourself a trainee hermit. Can you tell us more about this?

John Cleese

Because I think hermits would want to be given 20, what was it, seven years at all Souls. Because the fact is that if you are introverted and people always think if you’re a performer, you’re extroverted, it’s rubbish. I’m very introverted, as is my wife. And we’re never bored because introversion is a high level of activity here and introverts don’t like being overwhelmed by too much stimuli, whereas extroverts, poor things, don’t have much going on, so they desperately need stimulus or they get bored. I’m never bored. And the idea, like you said about your seven years, it All Souls, the idea that you could sit down one morning and start reading and suddenly thinking, I don’t know that word, I don’t know. And then you look the word up and that takes you somewhere else. You can spend the entire day without any time pressure, hopping around, looking at things that were interesting. That would be for me, the best possible day. If there was good coffee.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Absolutely. Well, yes. I mean, essentially, I’m an introvert as well. I was such an introvert that for years I’d go to neuroscience conferences and never ask a question. And now I do an enormous amount of performing, either in person or on Zoom or whatever, and I find it very comfortable. I’ve just learned how to do it. But people say to me, because I chose to live in a wild and beautiful place on a Scottish island, don’t you ever get bored? And I can honestly say I don’t know in my life when I’ve been bored, if given freedom. I mean, sometimes you can be held in a situation where you’re desperate to get out and you feel restless when.

John Cleese

You’re sitting next to someone. Dinner, really boring.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Boring, yes.

John Cleese

That’s when you get bored.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

That’s it. But actually, if you. If you’ve got the freedom to. I mean, even just sitting and staring out the window, the light is always different on the landscape. And there’s a marvelous Chapman, what’s he called, mid 19th century Russian writer who can’t remember his name now, but he said, all things will Pass. Except sitting in a chair and staring into the middle distance. And I often think about that.

John Cleese

I find now, in the last year or two, that if I can sit quietly and stare at trees, it makes me very.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Especially trees.

John Cleese

It makes me very happy. It’s as though just staring at the thing grounds me slowly, absolutely.

Mary Attwood

And that almost, maybe you travel through your eyes, your senses, and through the imagination that’s evoked through that. And there’s a lovely sentence in one of Gombrich’s books on the Renaissance. And he describes. I think it was Piero de Medici who had terrible gout and couldn’t move much at all. And he said that apparently in the later part of his life, when he really was quite immobile, would just sit in a room and ask to be taken to different rooms and sit there for hours just looking at the beautiful things they had in the books and admiring them. There’s something very lovely about.

John Cleese

That’s what happens when you look at a very fine painting. For me, you adore music.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Well, I do, yes. You don’t stare at music.

John Cleese

No, but you’re focused.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

But trees remind me of an interesting point, which is, you know, people always say, well, the point about beauty is it’s just to aid natural selection and so forth. And Darwin himself repeatedly made the point, once beauty exists, it can be used for whatever you like, including natural selection. But why does beauty itself exist? And trees make a point for me, which is their overall shape is colossally beautiful. The shape of an oak tree, the shape of a. Of a plane. All these things. And there can be no creature other than the human that can take in the beauty of it. Why does this have such a beautiful form for the human mind? I don’t know. I’m not suggesting an answer, but I’m just saying that the. We ought to doubt ourselves when we reduce everything to utility.

Mary Attwood

Yes.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Doubt ourselves very much.

Mary Attwood

Yes, absolutely.

Elizabeth Rovere

When you say that… It makes me think of the tree of life and the roots and the branches and how it grows and unfolds, and a leaf unfolds, and it’s just so beautiful. And then I was just passing this over to Mary, that there’s a quote from Charles Taylor, the philosopher, where he says that art is not an accessory to pleasure, but a means of our connection to the universe.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

Yes.

Elizabeth Rovere

And I just think that’s really beautiful about sitting down and taking something in, because you feel this kind of transcendent, if you will, connect.

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

And Thomas Nagel said that we don’t have values because we are conscious. We have consciousness because of values.

Mary Attwood

Right?

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

He’s an atheist. That’s lovely. I absolutely agree with that, that there’s something in the cosmos that calls to us and if it’s our job to respond to it and help it grow, or to ignore it and not know the purpose of being here.

Elizabeth Rovere

Thank you.

Mary Attwood

Thank you so much.

Elizabeth Rovere

Yeah, thank you. Iain McGilchrist, John Cleese and Mary Attwood.

John Cleese

Thank you. Oh, shut up.

Elizabeth Rovere

Thank you. I hope you enjoyed our first ever quad pod. I loved the interplay between Iain and John and it was my great joy to share Interviewing with Mary I can’t help wondering if humor is somehow fun, fundamental to consciousness, or at least intelligence. Thank you, Mary, John and Iain. And to you for listening. If you enjoyed this episode and think someone else might too, please rate the show and consider sending a link to your friend. We’re excited to hear your thoughts, share what resonated with you and leave us a comment. We look forward to hearing from you. Follow us @wonderstruckpod on Instagram. Subscribe to us on YouTube and your favorite podcast player and check out wonderstruck.org for more on guests and events. Wonderstruck is produced by Striking Wonder Productions with the teams at Baillie Newman and Creator Aligned Projects. Special thanks to Brian O’Kelley, Eliana Eleftheriou and Travis Reece. And remember, stay open to the wonder in life.